It was one of her first days back to work when she spotted it. The circle with X’s for eyes and a tongue sticking out of a crooked mouth. The band Nirvana’s logo on the shirt of student. The waves of grief threatened to overwhelm her, again.

“It was tough and I said a little prayer and then I got into my truck at about noon and I cried all the way home,” Donna Johnson said. “I thought, ‘That’s it. I’m never coming back. I can’t do it.’ But I can’t keep going from the bed to the couch to the couch to the bed.”

Johnson’s son, Jackson Warnick, 17, died of a drug overdose one month ago today.

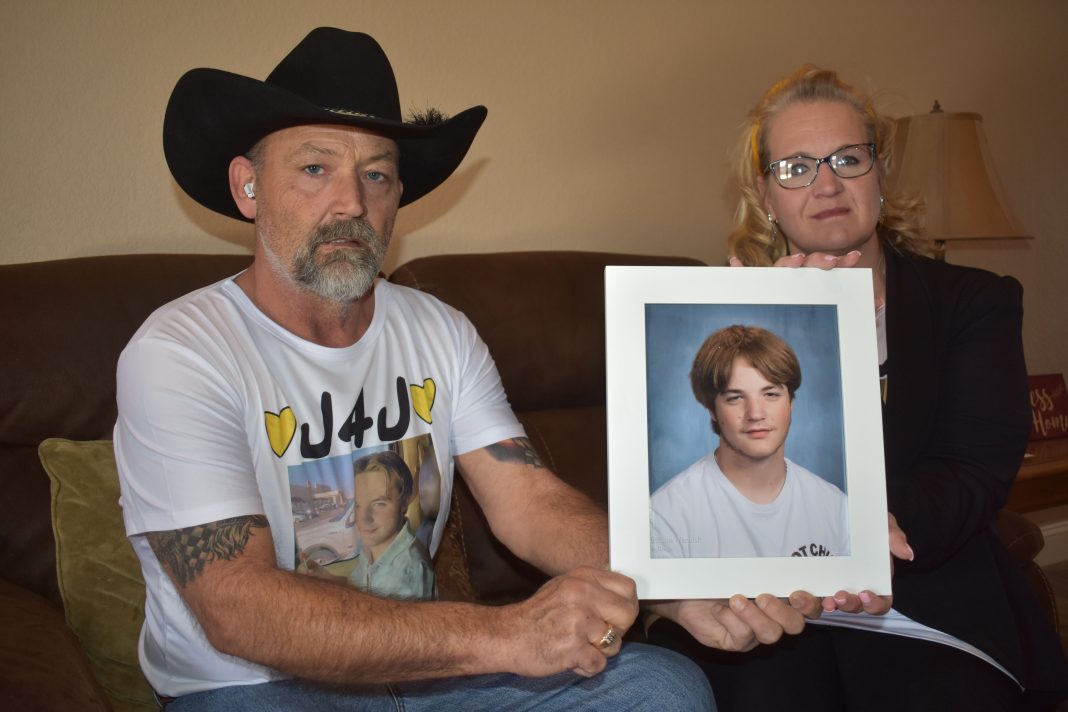

The ECISD elementary school teacher and her former husband, Joe, are now on a crusade.

They are determined to prevent another parent from going through the nearly unbearable grief they are experiencing.

They want every parent in Odessa to know what fentanyl is and just how lethal it can be.

Seventeen days after Jackson died Donna stood before the Odessa City Council and begged them to put her to work spreading the message. Jackson’s dad has written letters to lawmakers, sought an appointment with State Rep. Brooks Landgraf and asked Ector County Independent School District Superintendent Scott Muri to be placed on the school board agenda.

“Talking to you, talking to the city council and talking to Congress and trying to get something done and liquor is the only way I’m coping with my son’s death,” Joe said.

They’ve made shirts that say “J4J” which stands for Justice for Jackson.

They don’t want anyone to forget their son, a self-taught guitarist who could solve a Rubik’s cube in record time and had a penchant for making people laugh. He’d often wear absurd hats in public just to get a chuckle.

Nor do they want anyone to forget the way he died.

“We made that promise to our baby. Before they closed that casket, I held his hand and I kissed him and I said, ‘I hear you. Your mom is here and your mom is not going away,’” Donna said.

Jackson

Jackson came into the world early during a fishing trip to Del Rio and joined five half-siblings. After his parents divorced, he spent his time going back and forth between them.

The Permian High School junior hated school with a passion and he loved Nirvana, Sublime and the Red Hot Chili Peppers, but could just as easily jam to his grandfather’s old school country favorites. When he died, he was in the middle of penning his first song, “Never Fade Away” and he dreamed of becoming a rock star.

Jackson was not a highly social teenager, preferring a small network of friends and the solitude of his bedroom, his parents said. He often wore a shirt that said he was a member of the Antisocial Social Club.

“He’d tell everybody he suffered from anxiety and he couldn’t stand being in crowds, but if you ever got him out in the crowd, he was the life of the party. He made everybody laugh,” Joe, who is a salesman in the oil field industry, said.

Although he disliked school, Donna and Joe described their son as highly intelligent.

“He was just extremely smart and he never thought he was. I mean, you could tell him he was and he had argued with you,” Joe said.

Signs of trouble

The first signs of trouble came last year, Donna and Joe said.

First, Jackson got caught with a vape pen filled with tobacco. Then he got caught with a vape pen filled with THC, the active ingredient in marijuana.

The school suspended him and sent him to the alternative center both times.

His parents took his truck, cell phone, guitars and Xbox away from him for awhile each time.

Joe also started drug testing him and they both began tracking Jackson with a phone app. Joe regularly searched his bedroom and truck.

There were some times when they couldn’t track Jackson, but they believed him when he said his phone had died.

After Jackson tested positive the first time for THC, he continually tested negative.

Because Jackson had also started skipping classes and showing up late for work at a local pizza place, Donna and Joe started taking him to counselors and even a psychologist in Midland.

Jackson would sometimes say he missed classes because he fell asleep in his truck in the school parking lot.

The psychologist suggested various supplements he thought would help with Jackson’s insomnia and anxiety.

Unlike other teens they’ve heard about, Donna and Joe said Jackson didn’t argue or sulk over the appointments.

“It wasn’t like we took him kicking and screaming, but it wasn’t like a volunteer,” Donna said.

“I don’t think Jackson purposely tried to make anybody angry. He didn’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings. He’d tell you, you know, ‘You’re the best mom or you’re the best dad there is,’” Joe said.

Donna and Joe both remember not only having conversations with Jackson about drugs in general, but fentanyl, specifically. It’s a synthetic opioid that’s 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, it killed 110,236 people from September 2021 to September 2022.

They had both heard horror stories of people dying after taking “M30” or Oxycodone-laced fentanyl pills.

“I said, ‘You ever heard of fentanyl? If they put fentanyl in any of that stuff, it could kill you.’ He said, ‘Oh Dad, I’m not stupid. I know the difference. It would look different. It would look different.’ He just always thought he was too smart. He was too smart,” Joe said.

Donna even went so far as to record a Fox News interview with a distraught father who lost his daughter to a fentanyl overdose and texted it to Jackson.

“I get like an ‘OK mom’ or a thumbs up or just the letter K. Like, ‘That’s not me,’” Donna said. “We can’t tell you how many times we approached him about it and these kids just think it’s not going to happen to them.”

October

Things got rough at Donna’s house in October. One night, she and her husband, Larry, wanted to go out to a family dinner and Jackson refused. Jackson started throwing clothes into a duffel bag. Frustrated, Donna called police. An officer tried unsuccessfully to convince Jackson to stay, but ultimately told Donna they couldn’t prevent him from leaving given his age.

After a couple of days, Jackson called Joe and told him he was staying at his friend Sam’s house.

Shortly after that, Joe and Donna learned Jackson and Sam had been arrested for spray painting a pickup truck, causing thousands of dollars in damage.

Sam was bailed out of jail the same day. Jail records show Joe posts Jackson’s $4,000 surety bond the next day.

Jackson moved in full-time with Joe, but continued to see and text Donna regularly.

December incident

The first time Donna and Joe realized Jackson may have been using harder drugs than marijuana happened Dec. 29.

Joe was in Dallas waiting to have a double bypass and aorta valve replacement surgery when a friend of Jackson’s called one of his sisters to tell her Jackson was freaking out at their father’s house, thinking someone was trying to break in. When Jackson’s brother-in-law arrived, he found Jackson frantic and “out of his mind,” Joe said.

The police were called and didn’t find any evidence of a prowler or burglar and Jackson’s brother-in-law drove him to Dallas.

When Joe got home from the hospital, he and his daughter watched all of Joe’s surveillance tapes.

“He had actually gotten into my gun safe and got a pistol out and he’s walking around the backyard with this loaded pistol looking for somebody,” Joe said. “There’s nobody around that house and I don’t know what he’s hearing or what he thinks is going on, but you could clearly tell he was not himself.”

Jackson eventually admitted he’d taken LSD in pill form.

Once again, Jackson is grounded and Joe once again talks to him about fentanyl.

“I asked him what would have happened if they’d laced the acid and he said, ‘No, I know these people,’” Joe said.

Joe and Donna looked into admitting Jackson into a rehab facility only to discover that, at 17, they can’t force Jackson to go.

So, Joe continues to drug test Jackson, who appears remorseful, especially because of Joe’s precarious health situation.

When he wasn’t grounded, Jackson spent most of January at work or home, playing guitar and his Xbox, Joe and Donna said.

They thought Jackson was a typical teenager, pushing their buttons.

Tragedy

On Saturday, Feb. 11, Joe came home from work around noon because he didn’t feel well. Still suffering from a COVID-related cough and lethargy, he hit the sack.

Shortly before 5 p.m., he was awakened by a house guest saying there was something wrong with Jackson. She’d gone in to check on him because he was due at work at 5 p.m.

“The minute I jumped out of bed and my feet hit the floor I knew he was gone,” Joe said.

When he went to Jackson’s room, he found him cold to the touch with foam around his mouth and nose.

He started CPR.

It was too late.

Inside Jackson’s room the police found vials of urine along with cocaine and Oxycodone. They found M30 pills in his pockets and about 100 M30 pills in his truck, which Joe had searched just two days prior.

They also found a video on Jackson’s phone.

“It was created like 4:40 or something that morning where he takes cocaine and lays it out on a desk. He says he wouldn’t sell anything that he doesn’t do himself,” Joe said. “He got a rolled up dollar bill and he snorts these two big lines of cocaine.”

Authorities are still waiting for the results of toxicology tests to determine Jackson’s exact cause of death.

Aftermath

In the days after Jackson died, friends of his have come forward and identified people who were supplying Jackson with drugs.

One even told Joe and Donna of a TikTok video made by the girl who allegedly gave him the LSD back in December. She ridiculed Jackson for dying, saying he should have known he’d been given fentanyl-laced pills.

“The cops have investigated her and said she acted too immature to be a drug dealer,” Joe said.

Both Joe and Donna expressed frustration with the police investigation. They are chaffing at the length of time it’s taking to get the drug tests back and they want Jackson’s drug supplier arrested for murder.

“My problem is that now that the cops found that video, it’s like they’re through looking for anything else,” Joe said. “Somebody got him hooked on this stuff and had him selling it for them.”

Their son was not perfect, but someone needs to be held accountable, Joe and Donna said.

“I don’t want people thinking, ‘Oh, well, he did drugs, what do you expect?’” Donna said.

Investigation

Odessa Police Chief Mike Gerke and Special Operations Captain John Sikes said their hearts go out to Donna and Joe. It distresses them to know they don’t believe the department is doing its best to investigate their son’s death.

Nothing could be further from the truth, they said.

Although they can’t go into too many specifics, two different units are simultaneously working the case, the homicide unit and the drug unit, Sikes said.

“It’s listed down as an accidental overdose. Now, that doesn’t mean that there’s not a criminal offense that can be associated to it. In other words, if we can prove who did what, and who supplied it, which is a difficult venture in a lot of different ways, if we can prove it, we’ve put people up for that crime specifically in the past and we’re not afraid to do it again,” Sikes said.

At the moment, there is forensic testing being done not only on the drugs seized, but on Jackson’s electronic devices, Sikes said.

“I can’t imagine if it was my kid, but I’d be frustrated and mad too, but I mean, we can’t push the the evidence,” Sikes said.

Drug cases in general are hard to investigate simply because drug dealers don’t like to speak with law enforcement officers, but it’s particularly difficult when a major witness is deceased, Sikes said.

“We’re rooting out information and that often involves following up. We’re talking to one person and then corroborating that person’s statements and then so on and so on. It often turns into a web. Sometimes it falls into our laps, and most of the time it doesn’t because, again, drug dealers don’t like to tell their business most of the time,” Sikes said.

When there’s a social media component to a case, it can turn into a “rabbit hole,” too, Sikes said.

“We have to go and try to corroborate whether we believe it or not, which means whatever legal device we have to use to get it done,” including search warrants, Sikes said.

Detectives can absolutely know and believe something, but proving it is an entirely different thing, Sikes said.

“Our guys are following leads. They’re pushing forward. They’re asking questions and they’re collecting evidence,” Sike said. “But, any victim that has ever sat with me will tell you the same thing. I tell them every time, ‘I don’t promise you a thing in the world except for a thorough investigation.’”

Epidemic

Sikes said the “big three” drugs in Odessa right now are cocaine, methamphetamine and M30 pills.

“It’s a heartbreaking drug because it is killing kids and it’s killing kids that take it one time. You don’t have to be addicted. You don’t have to be an addict. It’s none of those other things that have stigmas attached to them,” Gerke said.

It’s for that reason OPD has been so busy trying to educate the public through such things as Neighborhood Watch meetings and social media.

“It’s a huge problem because it’s so deadly. I mean, when you look at other narcotics, you just don’t see the explosion in usage that you see with fentanyl right now,” Gerke said. “The other thing I’ll say about that explosion and the really troubling part to me is that you see that explosion of usage in younger people and in our school-age kids.”

At $20 to $40 a pill, kids can easily afford M30 pills, Sikes and Gerke said.

But, there is no such thing as quality control with fentanyl, Gerke said.

There’s no way to tell how much fentanyl is in an Oxycodone or Percocet pill that’s been laced with it, Gerke said. Somebody could take eight fentanyl-laced pills and be fine and somebody else could take one and die.

If officers find a bag of M30 pills, they’re instructed not to open it because they can’t predict what will happen when the fentanyl goes airborne.

“If we are running a search warrant and we expect fentanyl to be found, they’re all wearing the big bright white suits because it scares us to death,” Sikes said.

Nowadays, all officers carry cans of Narcan, an overdose medication, in their pockets, Sikes said.

The message OPD wants parents to have? Talk to your kids.

“Having hard conversations with kids? It sucks. I don’t like to have hard conversations with my kids. I don’t like having hard conversations with cops. But have those hard conversations, be nosy, know who their friends are and what’s on their social media. Take those extra steps,” Sikes said.

Gerke remembers getting lectures about drugs when he was a kid and thinking adults were just trying to scare him.

This is not that.

“With this, we’re not trying to scare you. We’re trying to inform you. This is dangerous and that’s why we’re saying ‘Just don’t take it. Just don’t,’” Gerke said.

Advice

Joe and Donna have plenty of words of advice they’d like to give other parents when given the opportunity. For one, they’d like to tell them to stand closer to their children when they’re submitting urine for drug testing.

Joe routinely stood five feet away from Jackson to offer him some privacy.

That decision haunts him.

“I wished I’d made sure. I was testing my kid and I never had any clue that he was doing what he was doing,” Joe said.

They’d also tell parents not to allow their children to put locks on their phones.

“Don’t trust everything your kiddo says. Be nosy, be snooping. Get in their social media, get in their phones,” Donna said.

Joe and Donna said they didn’t know until Jackson passed, but kids can actually communicate through their Xboxes, so they need to be monitored as well.

They also have suggestions for lawmakers.

The government shut down schools for COVID-19, but Joe suspects more kids have died from drug overdoses than the virus.

They’d like to see drug-detecting dogs in schools and better security at the border.

Neither Joe nor Donna have been able to go into either of Jackson’s bedrooms yet, but they’ve been taking solace from other family members and their faith in God. Donna has also gotten a lot of support from other local moms who have also lost their children to fentanyl.

Donna hopes one day she’ll be able to return full-time to the classroom without being “triggered.” Right now, she’s just substituting half-days.

“I still haven’t even been able to go to Andrews to visit his grave. I’m not ready. To me that’s just final, final and I can’t do it,” Donna said.

Want to know more?

If you’d like to know more about the dangers of fentanyl visit: tinyurl.com/n7ce89fw

In addition, the Odessa City Council will hold a discussion on fentanyl during its work session Tuesday at 3 p.m.