By MAGGIE PROSSER

The Dallas Morning News

Terri White woke up to an instant message from a relative on a Saturday morning last summer: Please call me, it’s about Mimi. It’s good news. White stirred and dialed the number about 8:30 a.m.

“They caught him,” the woman told White.

White had lost hope of ever hearing those words. Relief and joy and bitterness rushed over her.

Mary Hague Kelly, “Mimi,” was a vibrant woman and an avid Dallas Cowboys fan, said White, her granddaughter. Even into her late 70s, Kelly was active and energetic, “a force.”

The investigation into her untimely death stalled for more than 30 years, and life moved on; White married and had children, and eventually, her family abandoned Kelly’s season tickets to the Cowboys. Even as other decades-old crimes were miraculously solved, some of Kelly’s kin conceded her killer had seemingly gotten away with the heinous act.

But a groundbreaking technology — influenced by the boom of public interest in genealogy — cracked the cold case. Forensic genetic genealogy is transforming trendy DNA ancestry tests into crime fighting tools. The budding science garnered attention with the capture of the elusive Golden State Killer and has been credited with helping in hundreds of cases. The tech is not cheap, and now Texas Sen. John Cornyn and an area lab are working to make it more accessible and solve cases once believed to be unsolvable.

Kelly was a seamstress who designed high-end draperies and worked with Dallas’ premier interior decorators. Her west Oak Cliff home was an oasis for her family; White and her siblings spent sick days and summertime at their grandmother’s house. The family shared vacations and holidays. Kelly signed White up for dance classes, drove her there after school and sewed her recital costumes.

Kelly was 78 years old in 1989, and White was a soon-to-be bride. On a cool day that January, White was wedding dress shopping, browsing racks of cupcake gowns with balloon sleeves.

“It needs to have lace on it,” White told her shopping companion. Lace, to her, signified the classy style of her beloved grandmother. White toyed with the idea of Kelly making her dress instead of buying something off the rack. Ultimately, the women left and headed to dinner.

That night, White pulled into her driveway. She noticed, oddly, her parents’ car was gone, but her fiancé’s truck was there. White walked up to the door as her fiancé swung it open. He led her over to the couch and sat her down.

“I just knew something was wrong,” she recalled thinking, “and I knew that whatever he was about to tell me, I didn’t want to hear.”

Mimi is dead, he said.

White immediately assumed she’d died of natural causes given her age. But Kelly’s death seemed premature. Longevity ran in the family; the elders lived into their 90s. White’s fiancé went on to explain what happened: Kelly’s brother-in-law checked on her after she didn’t answer any calls. He found her stuffed underneath her bed, undressed from the waist down. She’d been strangled and raped. Her purse, some jewelry, an antique phone and her 1980 bronze Chevrolet Monte Carlo were missing. Detectives at the time saw no obvious signs of a break-in and only noted smudged dust near a lockless — but closed — window in the home’s back utility room.

Initially, the investigation tapped along steadily. There were some suspects and a slew of assaults against older women police thought may be connected, White said. Interviews turned up nothing concrete. Kelly’s killing attracted little media coverage; a review of The Dallas Morning News’ archive turned up one brief article about her death.

White married later that year. The ceremony was outside, and she wore a short dress with a poofy skirt, she said. At the bottom of her wedding program was an ode to her grandmother: In honor and memory of Mary Kelly.

“I got married and then had children and life went on,” White said.

A novel technology

By the turn of the millennium, the FBI created a national database to analyze unique genetic fingerprints from crime scenes against known DNA profiles. As of November 2022, the agency touted its database assisted in nearly 623,000 investigations and led to more prosecutions. But it is little help if the person’s DNA isn’t already in it.

In 2004, DNA found on Kelly’s robe was submitted to the FBI’s database. It yielded no matches. It would be nearly two more decades before technology advanced enough to catch Kelly’s alleged killer.

White held onto Kelly’s high school yearbooks and recipes, like her delicious chocolate meringue pie. She thought of her every holiday. White found respite in her faith, believing that someday she could forgive her grandmother’s killer, while others in her family struggled with resentment and agony.

“It became longer and longer in between contacting the Dallas [police] investigator,” White said. “We just kind of all came to terms that the person got away with it.”

“We just kind of gave up hope.”

Traditional DNA analysis has limited ability to identify relatives who share genetic makeup. For example, such technology may be able to link DNA to a suspect’s close relative — like a brother or father — but not a cousin or grandparent, according to Michael Coble, executive director of the Center for Human Identification at the University of North Texas’ Health Science Center. Coble spoke at a recent news conference hosted by Cornyn.

Novel forensic genetic genealogy analyzes tens of thousands to millions of DNA markers. Those results are then compared against genetic genealogy databases for people who share matching or very similar DNA patterns. Investigators can build a larger family tree of a suspect’s second, third or potentially even fourth cousins, Coble said. Coble’s public crime lab in Fort Worth recently became the first in the country to offer forensic genetic genealogy capabilities.

In 2018, California detectives used the science to arrest the Golden State Killer, a man who committed 50 rapes and 13 murders in the 1970s and ’80s and evaded authorities for decades. At least 500 cases worldwide are believed to have benefited from forensic genetic genealogy; one database chronicles more than 600.

The science has faced controversy and sparked debate about privacy and consent. Police can’t search some direct-to-consumer services, like AncestryDNA and 23andMe, without court approval, according to their websites. Sites like GEDmatch, which analyzes people’s DNA test results to connect relatives or build family trees, allow users to opt in or out of making their data public.

According to a 2019 interim U.S. Department of Justice policy, police should only use genetic genealogy services that “provide explicit notice to their service users and the public that law enforcement may use their service sites.” Additionally, the DOJ advises that information gathered from genetic genealogy is only an investigative tool, and traditional DNA testing and police work is required.

“It gives law enforcement the forensic lead they need to start crossing the T’s and dotting the I’s and bring people to justice,” Jim Walker said at the news conference. “This is a good day for us and a bad day for the perpetrators.”

Barrier to access

Walker’s 17-year-old sister, Carla, was abducted from her boyfriend’s car in Fort Worth after a Valentine’s Day school dance in 1974. Her body was found days later in a culvert, her blue formal gown partially ripped away. Her bra had been pushed up and her underwear, pantyhose and shoes were gone.

Fort Worth police arrested Glen McCurley 46 years later, in 2020, after DNA found on Carla Walker’s bra was sent to a private lab near Houston, and a genealogical database narrowed the search to three brothers, police said. McCurley, a neighborhood man, was an early suspect in the case and was interviewed a few weeks after Walker’s body was found. Although detectives didn’t have enough evidence to arrest him then, he remained a suspect for nearly half a century.

When he was tried for capital murder in 2021, Tarrant County prosecutors said it was possibly the first time genetic genealogy had been used in a trial. McCurley pleaded guilty to the killing midtrial and was sentenced to life in prison. He died in prison this summer, the Fort Worth Star-Telegram reported.

Forensic genetic genealogy was also used to identify the “Cowboy Hat Bandit,” a serial bank robber who shot a North Richland Hills police officer, as well as a suspect in the rape and murder of 11-year-old Julie Fuller, a database says. Dallas police arrested Edward Morgan in February 2022 after a genetic family tree pointed to him as a possible suspect in the 1984 slaying of Mary Jane Thompson, an aspiring model who was strangled with her own leg warmer. Morgan is charged with capital murder and is currently being held in the Dallas County jail.

“This technology is here so that families can get resolution,” Tarrant County District Attorney Phil Sorrells said at the news conference. “Now we can take that crime and link it to what was once an unknown suspect. … And that’s just a game changer.”

Sorrells took office after McCurley’s trial. The prosecutor, Kim D’Avignon, echoed the district attorney, saying, “we absolutely have the science now, we just do not have the funding.”

Forensic genetic testing is pricey; Coble, director of the Fort Worth lab, said it can cost several thousands of dollars to process a single case. Law enforcement agencies rely on private, for-profit and sometimes unaccredited companies for testing, he said. His lab’s recent accreditation allows it to provide free forensic genetic testing to Texas law enforcement agencies, lowering the barrier to access this technology.

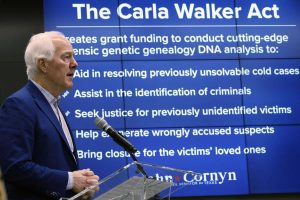

Cornyn, a Republican, said he plans to propose legislation to dedicate federal funding to help solve cold cases. Carla Walker is the namesake of the bill, which has not yet been introduced. Cornyn likened the impending legislation to the Debbie Smith Act that provides local and state crime laboratories with grant money to test backlogged rape kits.

“Scientists can do their job and come up with new cutting-edge technologies and answers to the questions that eluded us for years,” Cornyn said at the news conference last month, “but unless there are the resources — the money — in order to help pay for it, it’s not going to be widely available.”

‘A legacy of love’

Season of Justice, a nonprofit founded by the host of the popular true-crime podcast Crime Junkie, provided funding to the Dallas County District Attorney’s office to help solve Kelly’s case. A private lab created a DNA family tree in March 2022 from the unknown samples taken from the crime scene, which led police to David Rojas, according to an arrest-warrant affidavit.

Rojas’ family lived next door to Kelly at the time of her death. Kelly was last seen about 4 p.m. on Jan. 18, 1989, by Rojas’ half-brother who lost an unwieldy ball in Kelly’s backyard, the affidavit says. Kelly talked to the boy from behind her locked storm door and told him to get the ball, according to the affidavit. Some time later, a man allegedly entered the house and raped and strangled her.

Police staked out Rojas’ Del Rio apartment in the spring of last year. They watched as he threw away a six-pack of beer and then plucked a single glass bottle of Bud Light from the complex’s commercial-sized trash can. DNA collected from the bottle matched that from Kelly’s robe, according to the affidavit.

“Any technology that we can use that will bring justice to any of these people then I think we need to get behind and we need to support that,” White said. “That technology should be available readily for all law enforcement agencies to use for cold cases, for other families who have been victimized and have had to wait years and years. They should be able to get some closure finally.”

Rojas, now 54, was arrested on July 12, 2022. He’s charged with capital murder and is set to stand trial next year, according to court records. An attorney for Rojas did not respond to requests for comment.

“[Kelly] left behind a legacy of love and family and adventure,” White said. “When she was in your life, you were blessed.”