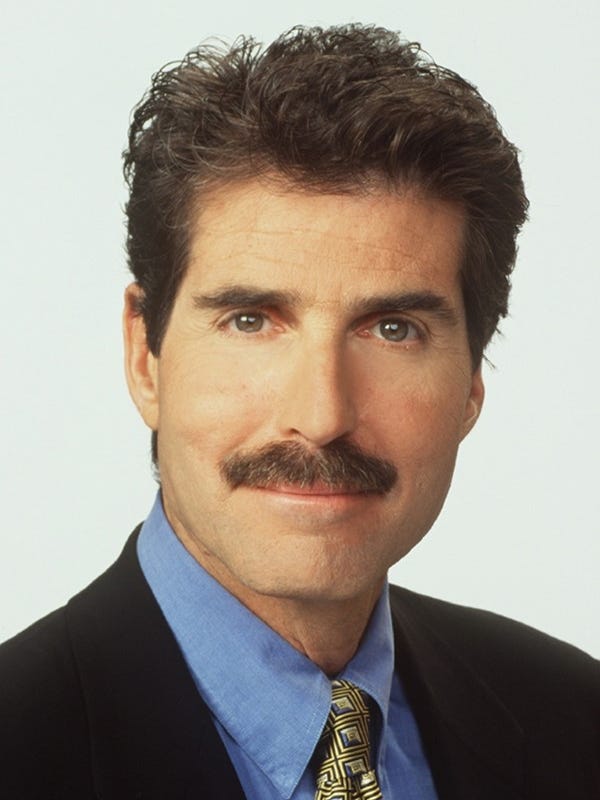

By John Stossel

The Fourth Amendment secures our right to be secure against unreasonable searches, right?

Not anymore, explains Naomi Brockwell on her popular YouTube channel.

In my new video, she explains how tech companies spy on us and then sell our information to the government.

But some of us actually find that tech companies prying can be a good thing.

Neil Chilson of the Charles Koch Institute says, “It’s not only good for the companies; it’s good for the user because it makes for a much more seamless experience.”

Apps can recommend places to eat, stores to shop at and much more.

These apps “make my life easier,” I tell Brockwell. “Convenience matters.”

“Convenience absolutely matters,” Brockwell agrees, “but privacy is important. … The U.S. government knows what color underwear you like to buy and what kinds of videos make you scroll a little bit slower.”

“So, what?” I say.

“That data is forever,” she points out. “Stored in permanent records associated with your identity in databases in Utah.”

Brockwell says, “You have no control over what regime might come to power tomorrow, over which hacker might get access to that data. You have no control over what societal norms might change in the next 10 years and that data suddenly becomes incriminating. You’re basically making a bet that you and the people with the guns (the government) will always stay on good terms.”

“What if they made cryptocurrency illegal? Made guns illegal? Everyone who partakes in that suddenly becomes a criminal,” she says, adding, “Look at what happened in China. Hong Kong used to be a bastion of freedom.”

When China crushed that freedom, they used people’s phones to track and punish protesters.

“Think about all the apps on your phone you’ve given permission to access your camera, location permission, microphone permission.”

“So they work better,” I reply.

“You are happy with these obscure apps, where you know nothing about the developers, to be able to look through your private photos?” she asks, incredulously.

I tell her, “I don’t think they want to look at my private photos.”

“That’s a presumption,” she replies.

“If they know where I am,” I push back, “They can recommend a ‘car repair shop near me’ or ‘restaurant near me.’ I like that.”

“I think it’s creepy, personally, but it goes further than that.” She replies, “These companies have a whole business model of selling that data. You have no idea where it ends up. … It could be ending up in the hands of hackers on the dark web who want to target you with phishing scams, in the hands of political regimes who want to target you with specific content to get you to think in a certain way. … And you’re probably oblivious that any of this stuff is going on.”

I’m oblivious unless I notice how specifically they market to me. I get creeped out when I’m talking about something and suddenly see an ad promoting something that addresses exactly what I was talking about. I think, “Oh, my God, were they just listening to me? How did they know to send me this?’”

“They know,” says Brockwell. “Did you give them permission to access your microphone?” she asks.

“Probably,” I say.

“They might be listening to you,” she says. More likely, they just know because they know where I’ve been, what I do, and who my friends are.

Brockwell then looks at my phone and tells me to delete most of my apps.

“But I like them,” I say.

“I know you like them,” She says, “but you are taking your phone around with you everywhere you go. … The government is purchasing all this data about us, creating records about all of us. That’s a really scary thing.”