During his campaign, Malcolm Hamilton presented himself as a home-grown athlete who reached the pros and then built a life as a successful businessman. These experiences, he said, qualified him to represent Odessa’s District 1.

“I’m used to dealing with pressure,” Hamilton said in an October interview. “I have experience in investment banking. I have experience in business. I have experience in negotiations, and that’s what a lot of this is about. It’s about being a liaison as well as a good communicator and I think I bring that to the table.”

But a closer look at Hamilton’s life presents a more nuanced picture at a time when the councilman finds himself amid ongoing controversy.

He was a star high school athlete who achieved an improbable rise to become a professional football player. His time in the National Football League was short lived. And it was followed by financial trouble and a series of career changes — including a stint in a sales role at a brokerage firm but not a job as an investment banker who raises capital for companies or other entities.

All led up to Hamilton’s return to Odessa and his pursuit of another long-held goal — winning public office.

A LONGTIME GOAL

Even nearly 20 years ago, Hamilton aspired to hold public office and shared this goal with the Odessa American when he was on the cusp of playing in the NFL.

“Actually, I want to come back to Odessa and be mayor,” Hamilton told a reporter back then. “I really do. That’s something I’ve really thought a lot about. I love Odessa. This is my home.”

Months later, in September 1997, Hamilton signed for the Washington Redskins practice squad.

Ultimately, Hamilton would play six games in the NFL before an injury in a Redskins game ended his NFL career.

During his 2016 campaign, Hamilton described his time as a pro athlete as a formative experience.

And so would some of his supporters, like former District 2 Councilman Jimmy Goates, who saw that experience as helpful for a prospective councilman.

“If you don’t learn teamwork in the NFL you don’t learn it anywhere and those are the types of things that I thought would help him out,” Goates, a fellow Baylor University alum, said.

After recovering from his injury, Hamilton played in the short-lived XFL for an Alabama-based team and for Arena Football League teams in New Jersey and California, last playing professionally in 2002.

AFTER THE NFL

Public records from this period, and in the years that followed, reveal Hamilton moved often. He worked at least 12 jobs during the past 10 years and faced a series of financial troubles.

In 2002, when Hamilton was living in Alexandria, Virginia, Virginia Management Inc. filed an eviction suit against him.

The State of California sued Hamilton in 2004 for $5,751 in back taxes. In 2009, when Hamilton was living in Dallas, the federal government filed a tax lien on him for $5,767.

And a year before Hamilton said he moved back to Odessa from Minneapolis, records show Willow Valley Limited Partnership filed another eviction suit against him when he was living in an apartment.

Hamilton said during his campaign that he lived in Minneapolis for about four years and moved back to Odessa in 2013. Before his time in Minneapolis he said he worked as a “salesman for oil and gas operators.” In Minneapolis, he worked stints for a debt collection company and buying and selling precious coins for a commission before finding an ad one day in the newspaper.

“That’s when I got into investment banking,” Hamilton said.

Hamilton said he was the managing director of “the interview advisory sector” of a “startup” company, known as a direct participation program.

It was a sales role. And per Hamilton’s LinkedIn page, the company was BrokerBank Securities and its DBA Redhawk Investment Advisors, and records show he worked there for about a year and eight months.

“Of course we struggled a little bit,” Hamilton said in the Oct. 5 interview. “I was stressed out trying to get it going. I had to train everybody on what to say, what not to say, what’s a good oil and gas deal. Me and the CEO we would bang heads every day. . . And I was just getting a lot of feedback from my investors. They said ‘Malcolm, really we are kind of leery of the fact the investment company is way in Minneapolis, Minnesota but the oil and gas wells you are investing in are in Texas.’ I said, ‘You know what? You are right.’”

‘I CAME HERE TO DO BUSINESS’

It was work Hamilton said he liked. And, Hamilton said in October, he wanted to move back home and work in “investment banking in oil and gas.”

“I came here to do business,” Hamilton said. “I ultimately want to open up my own oil and gas advisory company.”

More than three years after his move, Hamilton is not registered as an active broker, according to the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority, which is a corporation that acts as a self-regulatory organization.

As of October, Hamilton said he was studying for the Series 7 and another licensing exam that would allow him to trade more advanced financial products as a stock broker.

For now, BrokerBank Securities is the only company Hamilton has worked for as a registered broker, FINRA records show.

Instead, Hamilton’s LinkedIn page lists a series of oilfield jobs, mostly as a field service technician during his time in Odessa.

His page lists his most recent employer, from December 2014 to May 2016, as FMC Technologies.

It’s unclear what Hamilton does for work now. He listed “oil and gas industry” as his occupation on the form he filed with the city when he ran for councilman. He left the work number section blank and provided only his cell phone as his contact number.

Today, the top job Hamilton lists on his LinkedIn profile is his newest one: city councilman. City council members receive $10 per meeting they attend, capped at $50 per month.

HARDSHIP AND CHANGE

Hamilton moved to Odessa at age 4 and grew up in District 1, he said in October. As a child, he faced hardship, including the deaths of his mother and stepfather in elementary school.

By high school, Hamilton’s football position coach Mike Belew would find him “volatile,” with an “attitude and hostility” that Belew said he thought would limit the teenager despite his athletic prowess, according to a 1997 profile of Hamilton published by the OA.

But Belew also told the OA of the growth and change he observed in Hamilton.

“He’s a kid that went from having a very limited chance of making it to being real successful,” Belew said in that 1997 OA article. “He’s real intelligent and mature, and he’s one of those turnarounds you sometimes see as a coach. I definitely think he epitomizes that. I always use him as an example to my coaches and players as a kid who never gives up.”

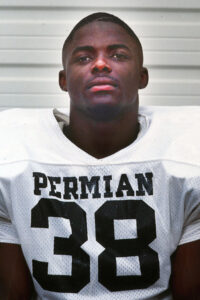

Hamilton was a star Permian High running back for a Mojo team that won state championships. His ability earned him a Baylor University athletic scholarship, where his performance on the field would earn him a chance at the pros.

But it almost didn’t happen.

A RIOT AND A SECOND CHANCE

In July 1992, before his first year in college, Hamilton was arrested during a riot at Whataburger. The riot, involving some 200 people, sparked a dialogue among politicians and community activists about minority policing in the city at a time when the country as a whole was reeling from the Rodney King beating.

The coordinator of Police Athletic League, where Hamilton volunteered, told the newspaper then that “one of the main people involved in this is Malcolm.” But the coordinator, Cpl. Henry Jackson, said Hamilton’s continued volunteer work helped kids process the riot.

Hamilton divulged his arrest during his campaign last year. He said he “got into a little scuffle with the police at Whataburger” but also told a reporter about the charges he faced afterward: aggravated assault of a police officer, inciting a riot and resisting arrest.

Hamilton said he had “never been in any other trouble since” and a public records search found no other criminal record.

In 1997, Hamilton offered this account about his “real stupid” behavior and said he later apologized to police:

“I was just trying to break up a fight,’’ Hamilton said. “A girl I was seeing at the time got involved, and a cop hit her with a flashlight. I was just trying to stop him from hitting her again, and I grabbed his arm to stop him. There were a lot of people out there, so I think it was just a reaction-type thing, but he punched me. Like I say, I don’t think it was really intentional because I’m sure he was scared and it was just a reaction. But I reacted, too, and punched him back.’’

Hamilton went to Baylor University as he awaited trial. And other prominent Odessans vouched for him. On Election Day, supporter Gene Collins, a community activist through groups including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, said he “helped him to get into Baylor” by talking with the school’s head football coach after the riot.

The felony charges were dropped, and Hamilton was ultimately convicted of misdemeanor resisting arrest and given six months of deferred adjudication that he served at Baylor.

His performance as a linebacker for Baylor led to his opportunity in the NFL. In his best and final college year, Hamilton played in all 11 games for the Bears, finishing with 45 tackles, two sacks and one forced fumble, according to OA archives.

“Everybody called me Dirty Mal,’’ Hamilton told the newspaper in 1997. “I admit it. I’m a dirty player. I’d bite, scratch, claw and kick, anything to get an edge. When I’m on the field I’m a completely different person than when I’m off it. It’s like you’re aggravating me to be in my presence.”

Hamilton graduated from Baylor in December 1996.

A DIFFERENT PERSPECTIVE

The wait lasted hours on Election Day before Hamilton learned he won the race for District 1 councilman, realizing a dream he held for decades.

“The people spoke,” Hamilton said that night. “They said they are ready for something new. Plain and simple.”

That was before the first few months — the grievances and suspicions about other city officials that Hamilton aired publicly without evidence, the curses he hurled at police during a traffic stop, the controversial taxpayer funded trip to Minneapolis, or the threat to pull city funding from a charity that doesn’t get any.

Among a handful of supporters in the Ector County Annex, Hamilton pledged that night to hit the ground running in pursuit of “so many projects” aimed at making the south Odessa district better like increased affordable access to the youth sports that helped shape him.

With him on election night was Collins who said he was confident in the promise of the new councilman.

Collins pointed to Hamilton’s broad range of experience and said the former pro football player’s background would help him connect with young people as a role model.

“He’s a product of the community,” said Collins, who Hamilton appointed Feb. 28 to the board of the Odessa Development Corporation and who did not respond to multiple messages left on his cell phone seeking comment for this article. “He sees even slum and blight through a different perspective with more passion because those are his folks … Being a sports hero coming back to your home town, you have a sense of obligation.”